MotoGP scoop: Ducati’s GP24 stripped! – Motor Sport

[ad_1]

Woollett told Redman that he’d been outside the Honda enclosure when he took the photos, so Redman had no right to take the valuable film.

Of course, Woollett wouldn’t have known that he’d really got the shot until he returned to the UK on Monday morning to get his films developed and file his report for MCN, which was (and still is) published each Wednesday.

Things were very different in those days. Woollett thought nothing of riding a Triumph Trophy sidecar (laden with typewriter, cameras, racing leathers and the rest) all the way to Salzburg for the Austrian GP (how many stops for roadside maintenance?!), shoot photos, write reports, take part in the sidecar GP (he was passenger for various riders over the years) then ride the Trophy home on Sunday night. And this was before the days of roll-on, roll-off Channel ferries.

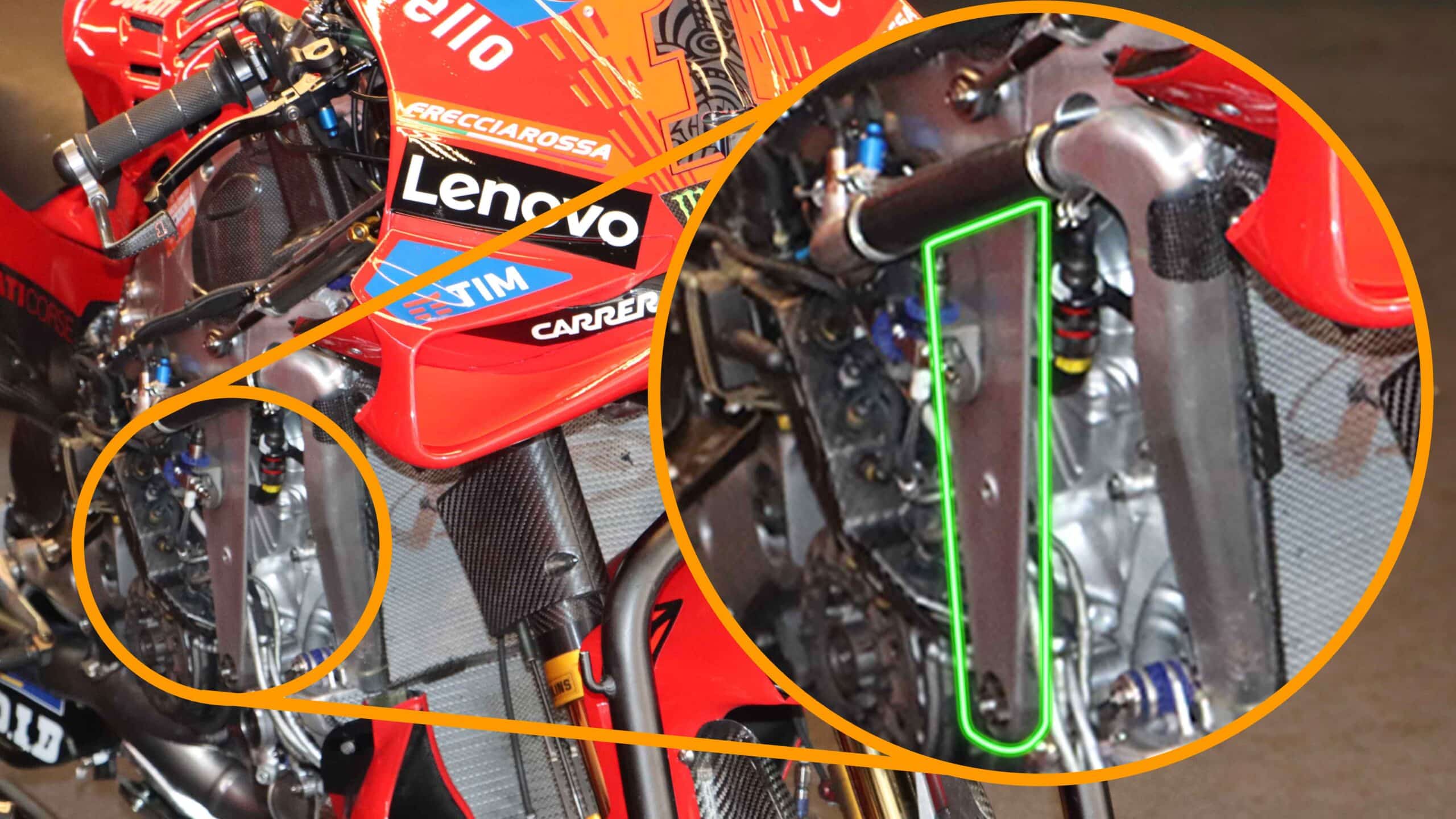

Anyway, back to the photo of the GP24 and what’s so interesting about it?

Look at the front engine hanger (the vertical aluminium alloy arm, partially hidden by a radiator hose). It is super-long and super-thin – much, much thinner than any engine hanger I’ve seen on a MotoGP bike.

It’s so thin – just a few millimetres thick – that it looks more like a cheap shelf bracket you might buy from a DIY shop. And it almost looks like it’s been stamped, rather than CNC-machined from solid, which is the norm.

At its top it carries the steering damper and is welded to the frame’s steering head section. At its bottom it’s bolted to the V4 engine’s lower front engine mounts (hence, engine hanger).

Why is it so thin? Because front engine hangers are an excellent way to create the lateral flex required in a racing motorcycle chassis.

A crashed 2022 Yamaha YZR-M1 shows the thin but very wide front engine hanger. The thinness creates lateral flex, for cornering, the width creates longitudinal stiffness, for braking and accelerating

Gold and Goose

When a motorcycle uses lots of lean angle through a corner, its suspension doesn’t really work, because it’s at such an acute angle to the road, but the rider desperately needs the bike to absorb irregularities in the road and continue to track the surface perfectly.

Therefore engineers build lateral flex into the chassis (lateral meaning left and right, which becomes up and down when the bike is on its side!), so the chassis flexes up and down at full lean, creating its own suspension movement.

If the bike doesn’t track the road, the tyres won’t grip the asphalt and if the tyres don’t grip, the bike runs wide and fails to turn the corner tightly and quickly, costing valuable time.

And what was Ducati’s age-old problem? Mid-corner turning. And this is what the rival engineer told me when I showed him the GP24’s super-thin engine hanger: “Lateral flex, for turning”.

Honda’s sublime 2002 RC211V was one of the first GP bikes to use longer front engine hangers to allow engineers to create lateral flex

Honda

The last Desmosedici I saw partially naked was a GP15, the first designed by Gigi Dall’Igna. The front engine hanger was a bit shorter, machined from solid and more than ten millimetres thick. The latest hanger obviously allows much more flex when the bike is leaned over. It’s almost certainly this feature that has played a part in the Desmosedici’s improved turning, which has helped the bike dominate in recent years, even though some bikes are still better mid-corner.

All manufacturers have gone thinner and thinner on various section of their frames and swingarms in search of controlled flex. If you flick some chassis parts with a fingernail they’re so thin – around 1.2mm – that they ping like a beer can, but usually this thinness is compensated by larger overall sections.

Take a look at the Yamaha YZR-M1 and you will see that the engine hanger is very wide, because while engineers want the bike to flex when it’s on its side they don’t want it to flex longitudinally (lengthwise, not sideways) when the rider is braking or accelerating, when upright or nearly upright, because this would cause problematic instability.

Therefore Ducati must have regained some longitudinal stiffness elsewhere to keep the bike stable. But I don’t expect they’ll tell me where or how!

[ad_2]

Source link

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/BBMHVBY5JZBRXDK6ALZ53CLQKM.JPG)